I am not writing this post only as a professional, but as someone who has just closed a ten-year cycle. On December 24, 2025, the core article of my doctoral thesis (defended in 2021) was finally published. Why did it take so long? Life, I suppose (and a need to catch my breath).

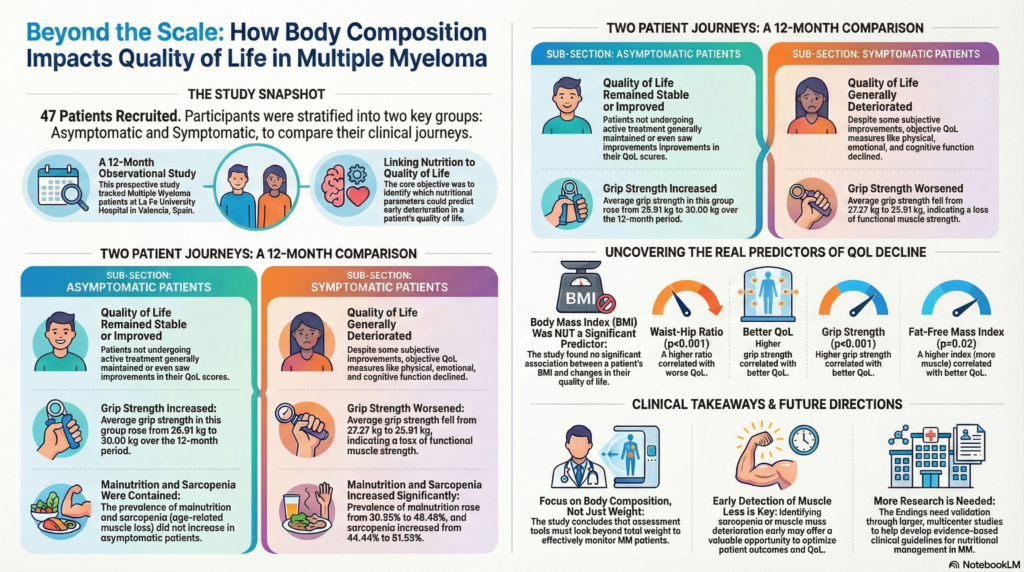

The article, Nutritional status, body composition and their relationship with quality of life prognosis in multiple myeloma patients: a prospective and longitudinal study (available here in PDF if you don’t have access), was published because it was a debt. It was a commitment to those who placed their trust in me. Thanks to those people, we can now use data to confirm a suspicion: body composition is a predictor of how one lives with Multiple Myeloma.

Why weight is a liar

Historically, oncology only cared if someone was losing weight. It was a quantitative perspective: If the scale doesn’t go down, «everything is fine.» However, this was only a half-truth. Today, we know it isn’t so much «how much is lost» but «what is lost.» This is where body composition and muscle mass assessment methods take the baton from that quantitative perspective; weight alone, without further detail, is an incomplete metric.

In our case, during a one-year follow-up of 47 patients with Multiple Myeloma, we observed that what truly impacted their well-being was not «just» the total number of kilos, but the quality of those kilos. This brings into play concepts that we must begin to normalize in hematology and oncology wards.

Of course, this is something already being included in some guidelines. But it certainly wasn’t the case in 2015–2016 when this work began, even though I already argued that it was important to look beyond weight (disclaimer: the post was only in spanish) using a then-novel criterion (the 2015 ESPEN criteria), which is now also a decade old. It seems obvious now, yet it still isn’t evaluated effectively in practice.

It is easy to say it’s evident now, but I assure you that in 2015, breaking the «weight-centric» paradigm was no easy task.

The muscle shield

In the study, patients with lower muscle composition indicators (technically, FFMIs or Fat-Free Mass Index) consistently reported a poorer quality of life. Muscle is not just for movement; it is a reservoir of «the to do things» spirit and an endocrine regulator. This can also be seen through its opposite: when muscle mass drops, there is more fatigue and poorer tolerance (higher toxicity and more symptoms) to treatments. Again, this is something already well-known for other diseases.

However, the quantitative metric itself is also insufficient, because by the time low muscle mass is evaluated, we are already arriving late. For this reason, we also used handgrip strength as a marker. The data was clear: the loss of strength preceded the worsening of quality of life. It is a simple, cheap tool that predicts deterioration at lower scores but, above all, helps us get ahead of the problem. If one day there is less strength, there is also less autonomy and a lower perception of health. Think of a day you have a fever or a cold; that reduction in the «capacity to do things» is how we define this reduction in strength, a «qualitative» parameter.

This is something that can now be prevented, flagging the «from the bed to the sofa» phenomenon before it occurs.

Study insight and disease evolution

The study divided patients based on whether the disease was active or quiescent (stable). Multiple Myeloma is one of the few diseases where you can compare those on frequent, limiting medication against those with the same disease who are not currently receiving treatment (acting as a control group). This methodological advantage allows us to isolate the effects of medication on nutritional status across different progressive lines of treatment.

Predictably, while asymptomatic patients maintained relative stability, those with active disease (symptomatic) suffered marked declines in body composition parameters over short periods. Theoretically, those in later lines of treatment were expected to have a worse general state due to time, so the progression in therapeutic lines (LdT in the study) should be understood as a timeline.

But among those with active disease, who worsened the most and why? Essentially, those who had less muscle mass (regardless of whether they had «classic» malnutrition measured by BMI), those with a larger waist circumference (excess fat mass), or worse muscle strength data. In other words, body composition variables explain who worsened much better than classic metrics like weight alone.

This indicates that nutritional intervention should be proactive, not reactive. We must not wait for the patient to lose muscle or weigh less than X amount; we must protect them from the moment of diagnosis, adapting guidelines to their starting situation with the clear goal of maintaining or improving muscle mass.

From the Clinic to practice

Whether you are a healthcare professional, a patient, or a family member, there are three essential points we aim to contribute with this work:

- Muscle predicts symptoms inversely, especially fatigue. More muscle is better. Preserving or maintaining muscle mass is the key, and this is achieved through sufficient intake. Using indicators to evaluate muscle mass ensures we have the information needed to prevent the gradual loss that age or treatments typically entail.

- The waist matters. Fat distribution influences treatment tolerance, fatigue, and general health perception. Reducing total fat mass in the context of «overnutrition» (overweight or obesity) is always a good idea. Something as simple as measuring the waist and setting its reduction as a goal provides vital information.

- Body composition changes faster than we think during active treatment. In these cases, eating well might not be enough. Sufficient nutrition must be combined with physical activity. Again, this sounds like common sense in 2025, but it was a «big picture» that was hard to see in 2015 (and remains a challenge today).

Ten years later, this article leaves the drawer to keep pushing the idea that nutrition in oncology and hematology (or is Nutritional Oncology?) is much more than «eating a bit of everything.» It is about nourishing a precise architecture where muscle is the load-bearing pillar of quality of life.

Limitations

Like everything in science, this study is not perfect. First, the sample size was modest (47 people), requiring caution when generalizing. We need larger studies to confirm these trends globally, but science is often won by «siege», showing a consistent global trend.

Additionally, while the technology we used (Bioimpedance and Dynamometry) is excellent for daily consultation due to its speed, there are more precise (though more costly and complex) methods available. Finally, treatments for Myeloma have evolved since we collected the first data; however, the biological basis remains the same: protecting your body composition will always be a safe investment, regardless of the treatment line or stage of the disease.

Graphical Summary – Click for better quality (Developed with NotebookLM, with subsequent human supervision and review.)

Deja una respuesta